HISTORY OF EPHESUS

The Neolithic Era and the Bronze Age Ephesus lies only 500 m. outside the eastern walls of the city. The recently excavated tell of Cukurici dates back to the 7th Millennium BCE. Austrian archeologists have identified at least 5 levels of habitation built one upon another in this humanly made mound. The site is not accessible for visitors yet.

.

In the 15th century BCE the fertile land near the mouth of the Kasytros River, on the western edge of the Hittite Empire, attracted Minoan and Mycenaean colonists. The Mycenaeans left evidence of their Bronze Age occupation on Ayasuluk Hill, to the north of the classical city. After the collapse of both the Hittite and Mycenaean cultures in about 1200 BCE, people named by Strabo as Carians and Lelegians lived in the area. They worshipped the Anatolian fertility goddess Cybele. In the 10th century BCE, according to ancient sources Androklos, the son of King Kodros of Athens, crossed the Aegean Sea, after consulting an oracle at Delphi, to found the city of Ephesus. The Ionians who followed Androklos started to worship local fertility goddess as indigenous people but they endowed her with identity of their own goddess Artemis.

.

THE ARCHAIC ERA

In about 650 BCE Cimmerians, attacked several Greek Cities. The Ephesian poet Kallinos, recognized as the first Greek elegiac poet, comb posed a patriotic elegy exhorting his people to fight the invaders: “It is honorable to fight for city and family, death finds everyone… For there is a longing among the entire people when the strong-hearted man dies, and while alive he is worthy of demigods.” The invaders razed Ephesus and desecrated the Temple of Artemis but were eventually drive out. Warriors then took control and ruled the city as tyrants. After a period of oppression, the citizens revolted and set up a council named the: Kuretes, thus initiating a more democratic system of government. For a few decades the Ephesians lived in peace as leading members of t Ionian League; their commercial and cultural life thrived.

.

In addition to Kallinos whose verse radiates nobility and bears similarities to the language of Homer., they produced the iambic poet Hipponax, famous for his biting satire and exposure of vulgarity in Ionian life. Another famous Ephesian, Heraclitus (or Herakleitos, ca. 535-475) made significant contributions to Greek philosophy. He lived after Thales of Miletus but before Socrates. Although regarded as obscure and pessimistic he is best known for his belief in the inevitability of change in the universe: “Everything changes and nothing remains still … and … you cannot step twice into the same stream.” His theory of the unity of opposites, and his thesis that all entities some to be in accordance with the logos have led to interpretations by many philosophers.

.

When Croesus of Lydia invaded Ephesus in 585 BCE, he destroyed the city and forced the citizens to move inland. Neverthe-less, he admired the Greeks and revered the Olympian gods. He supported the transformation of Cybele into Artemis and promoted her worship. With her new Hellenic identity, she became the emblem of Ephesus and brought renown to the city. Croesus, fabulously rich in gold, provided the funds to rebuild the Temple of Artemis on a grand scale. It stood only for two centuries but fell prey to arson. Croesus’s rule came decisively to an end when Cyrus the Great defeated him. The Persian King took Ephesus in 546 BCE and insisted on relocating it again.

.

THE CLASSICAL AND HELLENISTIC ERAS

In 336 BCE Macedonian forces threatened Persian hegemony. Philip II of Macedon sent his general Parmenio to conquer Ionian cities including Ephesus. The populace, anticipating his arrival, had overthrown the Persian satrap and Parmenio was able to take the city. He set up a statue of Philip in the partially rebuilt temple giving him equal status as Artemis. However, the Persians soon recovered Ephesus and destroyed the statue.

.

When Philip’s son Alexander the Great arrived at Ephesus in 333, it was the largest and most powerful city in Anatolia. Mercenaries guarding it had learned of Alexander’s triumph in the battle of Granicus and fled leaving the citizens to welcome him.

.

Finding a new temple to Artemis under construction, Alexander offered to pay for its completion, but the Ephesians, troubled by his desire to dedicate it to himself, employed flattery to dissuade him. They said it was improper for a god to make offerings to a god. While in Ephesus, Alexander made a momentous change in his policy. Emissaries from nearby Magnesia and Tralles told him that their cities had thrown off the Persian yoke and established democracies. Their message proved persuasive. From that pivotal moment, he favored independence and self-government for Greek cities.

.

Alexander’s successor, Lysimachus, moved Ephesus to its present position. To achieve this relocation against the will of the residents, he resorted to blocking drains after a violent rainstorm in order to flood them out of their houses. He also forced the inhabitants of Teos, Colophon and Lebedos to join them on the new site to create a larger metropolis. The city then developed along a road winding down a narrow valley between the mountains Koressos (Bulbul Dag) and Pion (Panayir Dag) and spread out on more level ground by the harbour. In this more salubrious position away from the marshes Ephesus thrived. Although the city flourished, it suffered bloody episodes, as a series of rulers fought over it. In 188 BCE after the battle of Magnesia, in which Rome and Pergamum opposed the Seleucid ruler Antiochus III, King Eumenos of Pergamum took Ephesus.

.

ROMAN & EARLY CHRISTIAN EPHESUS

After death of the Pergamene King Attalos lll, who willed his empire to Rome, membership in the Roman Empire brought peace. Under Augustus (63-14 BCE) Ephesus entered a Golden Age; it became the capital of the Roman Province of Asia and the second largest city in the Empire. An invasion of Asia by the Politic King Mithridates completed in 88 BCE briefly interrupted Roman control, but the Roman General SuIla drove him out and restored Roman rule. By the year 100 CE the population reached at least 200,000. The fame and status of the rebuilt Temple of Artemis increased, enriching the silversmiths who produced and exported effigies of the goddess. The well-placed harbour and the Royal Road, built by the Persians to the Anatolian interior, encouraged trade

not only in goods but also in slaves. Indeed, Ephesus became the slave trade capital of the Mediterranean as well as the banking center of Asia. Citizens amassed wealth and displayed it by building grandiose of structure in honor of emperors. Even former slaves with talent and enterprise could excel there. For example, two freedmen Mazaeus and Mithridates built the impressive gateway beside the Library of Celsus in honor of Augustus and Agrippa.

.

Since the early days of Greek settlement, the temenos (sanctuary) of Artemis gave the right of sanctuary to any who took refuge within its boundaries. Alexander extended the area to a distance of One stade (a little under 200 m.) from the temple. Mark Antony enlarged it further to include part of the city, but Augustus, responding to complaints about the miscreants causing trouble under this protection, reduced it again. Cleopatra’s half-sister Arsinoe was one of those, who took refuge in the temple after Julius Caesar had exiled her to Ephesus. Nonetheless, Cleopatra persuaded Mark Anthony to order her murder.

.

In the late first century CE a distinguished Ephesian physician, Soranos made significant strides in medicine. His writings, including his treatise on gynecology and his book On Acute and Chronic Diseases, which still survive, offered a deep analysis of biological functions. Only Galen, the Pergamene physician who lived after Sopranos’ death, surpassed him.

.

Ephesus played an important role in the development of Christianity in Anatolia. Since the cult of Artemis remained popular and received imperial support, Christians encountered fervent opposition. St. Paul came there in 58 CE and met with a small Christian community, including Timothy, whom he chose as companion on several journeys. They made the city their base for missions in Asia and to Corinth. In 65 CE Paul consecrated Timothy as Bishop of Ephesus, a position he held until 97 CE when an angry mob beat him to death for trying to stop a procession honoring Artemis. Earlier, Paul himself barely escaped martyrdom when, after preaching against idolatry, he inflamed the silversmiths by denouncing their trade in figurines of Artemis. Only the prudent words of a city official calmed the angry crowd that gathered in the theatre. In the fourth century CE, under Constantine, who legalized Christianity, and Theodosius I who mandated the Christian faith as the sole religion of his empire, Ephesus became a Christian city.

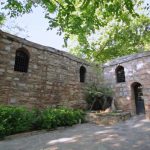

Many believe that the Virgin Mary ended her days in Ephesus. Since Jesus, on the cross, charged the apostle John with the care of his mother (John 19:26.27) and John is thought to have written his version of the gospel in Ephesus. On the other hand, a competing tradition places her death in Jerusalem. The house identified as the House of Virgin Mary could possibly be the site of her last dwelling, though it is of Byzantine construction. The main testimony that she lived there came in visions experienced by a Bavarian nun, who provided convincing descriptions of the place. Popes Paul VI, John Paul II and Benedict XVI have all given credence to the story by celebrating mass there.

.

In 431 about two hundred bishops attended the third Ecumenical Council of the Early Christian Church in Ephesus to resolve the heated argument between Nestorius, Patriarch of Constantinople, and Cyril, Patriarch of Alexandria over the divine and human natures of Christ. Nestorius believed his two natures to be distinct and asserted that the Virgin Mary could be called the Mother of Christ but not the Mother of God. To great rejoicing of Ephesian Christians, Nestorius was defeated. The council took place in the Church of the Virgin Mary, an immense building created out of a ruined basilica and altered several times since. Early in the fifth century Christians built a vast cruciform church almost 80 m. long over the tomb of St. John on Ayasuluk Hill.

.

Meanwhile the relentless action of the Kasytros River impeded navigation by silting up the harbour. Nero ordered an ambitious dredging project and, after the attempt failed, Hadrian diverted the course of the river. But imperial decrees could not overcome the forces of nature; by the third century the harbour lay three miles from the sea and malarial swamps threatened the health of the population. In 359 CE an earthquake caused serious damage in the city, for example destroying the upper cavea of the theatre. In the late Roman period, as Ephesus declined, political strife prevailed.

Source : Henry Matthews – Greco-Roman Cities of Aegean Turkey